Researched and Compiled by David Meinert

Tilikum Place, a small park in the Northwest corner of Seattle’s central business district, holds one of Seattle’s oldest works of public art, a life sized bronze statue of Chief Seattle named “Seattle, Chief of the Suquamish“. Chief Seattle is the city’s namesake, chief of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes. The site on which the statue and fountain are located commemorates the ties of friendship between the white settlers and the Northwest Indian culture that greeted them when they arrived in the 1850’s. The triangular intersection was named was placed near the point where the boundaries of the original claims of Carson Boren, William Bell, and Arthur Denny met. “Tilikum” is a Chinook word interpreted variously as “tribe, people, relations, and friend” and also denotes greeting or welcome. Coincidentally, Tilikum Place is at the edge of the area that was for many generations known as Potlach Meadows, scene of Indian feasts and games. Potlatch Meadows is now the site of Seattle Center. Also, Cedar Street honors the coniferous tree so important to Chief Seattle’s people; they carved its wood into dug-out canoes, split its boards for their houses, and wove baskets and clothing from its bark and fibers.

Approximately 460 square feet in its original form, Tilikum Place has been increased significantly by the addition of the partially abandoned right-of-way of Cedar Street. After the Denny Regrade of 1905, this plot was set aside as a memorial site named Tilikum Place. The word Tilikum means “welcome” or “greetings” in the Chinook dialect.

The focus of Tilikum Place is the life sized statue showing Chief Seattle facing Elliott Bay with his right arm raised in greeting. His height of six feet was based upon Daniel Bagley’s memory. He recalled, “I stand about 5’8″ and I know the Chief was inches above me.” The Chief’s costume is a four point Hudson’s Bay blanket, his habitual attire.

In addition to the statue itself, there are interesting pedestal ornaments designed and cast by the statue’s sculptor. These include two bronze bear heads that served as fountain spouts. A triangular plaque above the south-facing bear head is inscribed with the name Tilikum Place and stylized letters that identify Tilikums of Elttaes, the sponsors. On the east side of the pedestal, a bronze plaque depicts in low-relief the sighting of Captain Vancouver’s ship by the Indian Kitsap in 1792. On the west side of the pedestal, another bronze plaque is inscribed: “Seattle, Chief of the Suquamish, a firm friend of the whites, for whom the city of Seattle was named by its founders.” Two dolphins frame a sea shell with the date 1908.

The work was the city’s second piece of public art (the first one was a totem pole erected in 1899 in Pioneer Square), and was sculpted by Seattle’s pioneer sculptor, James Wehn.

In 1907, the city budgeted monies for street improvements in the newly regraded area, including funds for a sculpture to mark the historic site. Ordinance No. 16774 had originally allocated monies for the statue. On March 28, 1910, a second ordinance, No. 23705, was approved “to appropriate money to complete the construction of the fountain and statue at Fifth No., Denny Way, and Cedar Street.” But sources disagree whether the City funded the entire project or if a committee of local businessmen appointed to oversee it came up with the funds. The committee included city engineer R.H. Thomson, and Clarence Bagley, then secretary of the Board of Public Works.

Either way, the committee came to be known as the “Tilikums of Elttaes” (and were forerunners to the Seafair Pirates) who dressed in red-face and traditional costumes of local Native Americans, highlighting the accepted racism of the time, especially by city leaders. A famous photo of a group of Native American men dressed in traditional regional Native attire at the dedication ceremony is actually a photo of the “Tilikums of Elttaes”. The Tilikums of Elttaes exploited local Native art to promote the city, and promoted an annual festival called “Potlatch Days“, featuring a Grand Parade in which various Seattle playgrounds entered units or floats and the sponsorship of “historic projects” (of which Tilikum Place was one). The first parade was in 1911 and continued for just a few years. It was renewed in 1949 as Seafair.

The original proposal for a sculptural fountain including a horse trough was made by the architectural firm of Kerr and Rogers. Their concept was a classical figure of Mercury bringing riches from the Orient. The committee’s indecision led Rogers to recommend they discuss the project with sculptor James Wehn, then 24. After conferring with Bagley, whose focus was local history, Wehn abandoned the Mercury concept and instead proposed a full sized portrait of Chief Seattle.

This idea was enthusiastically accepted by the committee and Wehn started modelling the form.

Wehn received the official nod from city leaders in early 1908, and spent the next five years completing the statue and its accompanying relief plaques. With the encouragement of Msgr. F.X. Prefontaine, Wehn established a sculptor’s studio (Seattle’s first) in back of his family home near Mount Baker district.

At the insistence of the pioneers on the design committee, the original design for the statue included a full size canoe. However, after the first casting proved inadequate, Wehn eliminated the canoe maintaining it was “not artistic.” According to his own recollections of the commission, the task would have been too complicated, especially since the single figure had to be cast in New York City and was several years behind schedule at the time.

Wehn did meticulous research and numerous studies of Puget Sound Indians in preparation for the Chief Seattle statue and used the only known photo taken of The Chief in 1864. During 1911, Wehn travelled to Indian villages, studying Indian physical characteristics. He based his design on different live models. Wehn finally completed a clay figure from which a plaster cast was made in 1912

The work did not go without complications. One visiting Indian posing for the body of the model noticed a skull recovered from a local burial ground in Wehn’s studio, and never returned. And then, despite When’s insistence that an experienced East Coast foundry cast the statue, the committee had awarded the contract to a local firm in 1908; the results were unacceptable to the artist. Concerned for his reputation, Wehn asked the committee to change foundries. The committee refused, so he destroyed his plaster cast. As Wehn related it,

“I went to the foundry. I told them there was to be no statue. That as far as I knew they were through and possibly I was too. The foundry was built about five feet above tide water. With the help of a borrowed wheelbarrow, I proceeded to dump my plaster cast into the tide water. Later that afternoon, I went to Dr. Chrichton’s office to tell him what had happened. Shaking his head as he shook my hand, he said, ‘Maybe it is for the best.’ I proposed that I would model a new statue; but I was to have a free hand.”

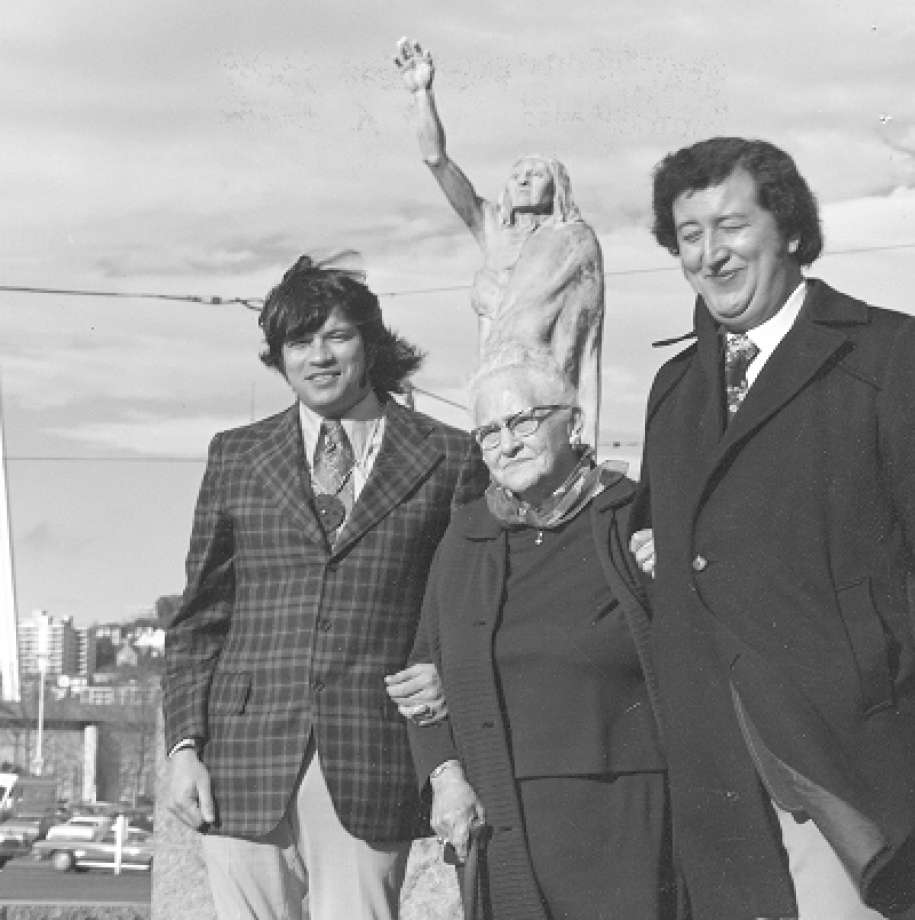

Wehn then made a new life sized model, first in clay then in plaster, and sent it to Providence, Rhode Island, for casting by New York based The Gorham Manufacturing Company. Finally on November 13, 1912, Myrtle Loughery, Chief Seattle’s great-great granddaughter, unveiled the finished sculpture on Founder’s Day in an impressive civic ceremony as part of Potlatch Days.

Potlatch Days has an “interesting” history. The Seattle Chamber of Commerce, the Advertising Club and the Press Club decided to create a civic celebration loosely modeled on the Northwest coastal Indian tribes’ potlatch, a ceremony of friendship and sharing. Seattle held its first Potlatch in 1911, but the Golden Potlatch of 1912 was a far greater festival, meant to attract visitors from far and near. The summer carnival was both a cynical exploitation of local Native culture, and a madcap spectacle. The Potlatch shamelessly looted the heritage of Pacific Northwest Indian people. The Golden Potlatch began with the arrival of the ‘Hyas Tyee’ — or Big Chief — in his great war canoe, visiting the city from his home in the far north. The Tillikums of Elttaes (Seattle spelled backward) paraded the streets in white suits, their hats draped in battery-powered lights, gladhanding any visitors who came their way. Bright-eyed members of the Press and Ad clubs, as well as the Chamber, slathered themselves in greasepaint, donned Chilkat blankets and pretended to be ‘tyees‘ and ‘shamans.’ But the Golden Potlatch volunteers also offered a week of entertainment free to anyone in the city. Every day there was a different parade downtown — of the fraternal orders, the labor unions, the soldiers and sailors, or Seattle’s children. Daredevils flew ‘hydroplanes’ over Elliott Bay, and warships from the U.S. Pacific fleet anchored in the harbor. In 1913, the festival lead to the Potlatch Riots.

In 1920 the spouting bear heads were officially turned off, the basin around the pedestal drained, filled wtih earth, and planted with ivy, the “old horse tub” drinking fountain removed, and the triangle repaved and recurbed.

Eight years later in 1928, a major remodeling was contemplated: to place the Chief on a new and higher pedestal, night lighting, and new plaza. James When was called in as consultant and endorsed the basic concept. Before the Park Board could act, it sought and was granted jurisdiction of the statue. Evidently the only work accomplished was to replant the basin and install night lighting. “We have decided not to remodel the base … at this time.”

In 1936 the West Seattle Legion, Lions and commercial clubs proposed the relocation of the Chief’s statue to a “more appropriate location (at) Duwamish Head.” Their proposal was denied and remained dormant for 20 years, when the Teamsters Council (whose office was adjacent to Tilikum Place) took up the proposal. According to the Teamsters, the statue was not in a prominent location for tourists OR resident to find. The Teamster proposal was at the point where Aurora Avenue entered the new subway to the waterfront viaduct. This time the proposal went to the Municipal Arts Commission. Seattle University promptly made a bid for the “Chief”. The Commission considered seven sites as suitable locations, recommending Denny Park as number one, but finding Pioneer Square as “very suitable” but not recommended owing to the con- troversy over rehabilitation of the square and district. Opinions were solicited and offered from many groups and persons, including Pioneer associations. The “predominant suggestion was for the status to remain . . . for the present.”

In 1958 the first graduating class of Sealth High School inaugurated a senior class tradition with clean-up ceremonies for the statue – approved by the Park Board and James Wehn.

By the 1960’s, the statue and surrounding site were badly in need of care; the bear heads no longer spouted water, the pool was filled with plants, and the statue had accum¬ulated years of grime. The statue was removed and cleaned prior to the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962.

Then came Seattle’s second exposition – “Century 21 World’s Fair” and a monorail car line built “behind the Chief’s back!” So the movers became vocal again: “at least turn the statue to face the Monorail or Fairgrounds.” Instead, the old basin was cleaned out and new jets and underwater lights added, the bears spouted again, the “triangle” was enlarged and repaved, trees and benches added.

In 1971 the Native American students of North Kitsap School sought to move the “Chief” to Suquamish for proper care and appreciation. After unsuccessful proposals to move the statue to locations such as Duwamish Head, Denny Park, and Pioneer Square, the statue was removed for cleaning in anticipation of the Century 21 Exposition of 1962. Wehn objected to a proposal to turn the statue around so it would face the then-new Seattle Center Monorail. After its cleaning, the statue was returned to its original location and orientation, facing Elliott Bay.

A contract for rehabilitation of the site and the fountain pool was awarded to the firm of landscape architects Jones and Jones in 1975. They were hired to enlarge the triangular site, design new lighting, surface paving, street furniture, and plantings. The site was rededicated on December 8, 1975. By closing Cedar Street to traffic and paving it and the triangular site of the original park with unit pavers, Tilikum Place became less an island surrounded by traffic and more a vest pocket park protected by small-scale early twentieth century retail and apartment buildings—several of which have recently been restored and repainted. The borders of the park are planted with 11 Sycamores. The site also features ornamental metal tree grates, unit pavers, and single globe lighting standards designed to be utilized in future Denny Regrade parks and open spaces. Along the Cedar Street side of the park are four narrow wooden slat benches. Sixteen cylindrical concrete bollards define the trafficked perimeters of the triangle.

The fountain pool has been enlarged from its original design, its three-tiered circular granite steps were designed to allow for more interaction between people and the statue. The granite is smooth on its top surface and rough finished on its sides. Two 12 ton granite boulders were shaped by Seattle sculptor Richard Beyer to fit into the rim of the pool. The artist also chiseled petroglyphs on the surfaces of these boulders. Surrounding the granite pool is a circle of square granite pavers enclosed by an ornamen- tal metal ring. Due to the recent alterations to the pool and Tilikum Place, only the statue of Chief Seattle and its embellished base are considered to be historically significant.

By 1980, the statue had turned green. A local taxi driver attempted to clean it himself, scratching it and exposing its original bronze color. A subsequent restoration revealed that the statue originally had been gilded (covered in gold leaf).

The “Seattle, Chief of the Suquamish,” statue was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in April 1984 and is located in King county.

In December of 2008, nearby residents Carole Jordan , John Nagy, and John Pehrson worked together for two years to raise $16,000 for the lights to be added to the statue and the park to get the city to leave them on year round.

In 2010, when David Meinert purchased the 5 Point Café, the infamous 24 hour diner and dive bar on the edge of the park, he was able to get the city to add some tables and chairs to the park, and expand the 5 Point Cafe’s outdoor seating into it as well, winning out over the objections of neighbors who thought the seating would disturb the neighborhood due to the restaurant’s notorious customers.

James Wehn went on to found the sculpture department at the U.W. in 1919 where he taught for five years. He sculpted the Chief Seattle drinking fountain (with bubbler for people and basins for horses and dogs) from which three copies were cast – one placed in Pioneer Square, one placed here was relocated at Westlake and vanished, and the third was placed at the depot and was moved to the yard of the Renton Fire Department, In 1936 Wehn was commissioned to design the official City Seal and made an large version to fit for the Public Safety Building in 1950. He did a bust of the Chief for Seattle University. His many works can be found in museums and public buildings in Washington and Alaska. A permanent collection of When’s work is housed at the Washington State Historical Society Museum, Tacoma. He served on the Seattle Arts Commission in 1956, coincidental with one of the controversies relocation of the Chief’s statue.

– By David Meinert